Forests are known by many names: rainforest, woodland, wood, jungle, bush, backwood, park, with each term conjuring its own meaningful subtext.

Forests are known by many names: rainforest, woodland, wood, jungle, bush, backwood, park, with each term conjuring its own meaningful subtext.

Woodland, to the fanciful mind, might imply the existence of a realm of unseen beings who sleep sheltered within the center of a daisy or owe their existence to the lifeblood of an oak older than Shakespeare. Jungle might bring to mind a lush emerald-green canopy, howling monkeys, primeval flowers luring insects to their doom. Backwood may evoke a place where few people go except to party, poach, or perhaps dispose of their toxic waste.

Human notions about forests, be they whimsical or prosaic, sometimes miss the mark. One of the most common misconceptions is that a forest can be replanted. Where they have been cut down, trees can be replaced. But a forest is not only an ecosystem, it is an organism that, once lost, is gone forever.

Tree roots extend a long way, more than twice the spread of the crown. So the root systems of neighboring trees inevitably intersect and grow into one another—though there are always some exceptions. Even in a forest, there are loners, would-be hermits who want little to do with others. Can such antisocial trees block alarm calls simply by not participating? Luckily, they can’t. For usually there are fungi present that act as intermediaries to guarantee quick dissemination of news. These fungi operate like fiber-optic Internet cables. Their thin filaments penetrate the ground, weaving through it in almost unbelievable density. One teaspoon of forest soil contains many miles of these “hyphae.” Over centuries, a single fungus can cover many square miles and network an entire forest. The fungal connections transmit signals from one tree to the next, helping the trees exchange news about insects, drought, and other dangers. Science has adopted a term first coined by the journal Nature for Dr. Simard’s discovery of the “wood wide web” pervading our forests.1

Just as ninety percent of an iceberg lies unseen, so does a forest. The root systems and fungi can be compared to the neurons of a mammalian brain, and these networks take centuries to grow. Trees parent, nurse, teach, inform, congregate, isolate, feed, breathe, compete, and help. This is what they do for their forest kin. In addition, every forest on Earth provides oxygen, food and shelter for all her fauna.

Forests also provide food for spirit and imagination.

Buddha was one of the god Vishnu’s incarnations, and it is told that in his youth he was never so happy as when sitting alone in the depths of the forests lost in meditation; and it was in the midst of a beautiful forest that he was shown the four great truths.2

They figure in a multitude of stories, legends and epics: Gilgamesh, Merlin and King Arthur, Robin Hood, Dante, Shakespeare, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Fangorn Forest and Mirkwood, C.S. Lewis’ Narnia, Kenneth Grahame’s Wild Wood, J.K. Rowling’s Forbidden Forest, Max’s room in Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are.

The woods make murky the boundary between reality and fantasy.

There is a tradition that when Napoleon, during his Russian campaign, had, after leading his army three times running against the Monastery of the Holy Trinity, near Moscow, arrived at the gates of Tröitsa, a thick forest suddenly sprang up before him.3

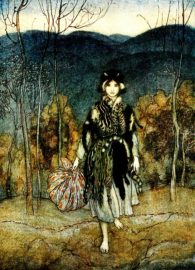

It’s no wonder forests are symbolic of the unconscious realm and figure in many fairy tales.

Since ancient times the near-impenetrable forest in which we get lost has symbolized the dark, hidden, near-impenetrable world of our unconscious. If we have lost the framework which gave structure to our past life and must now find our own way to become ourselves, and have entered this wilderness with an as yet undeveloped personality, when we succeed in finding our way out we shall emerge with a much more highly developed humanity.4

Dark Dark Woods from The Animation Workshop on Vimeo.

The forest is both alien and familiar, a place of exile that can be at once dangerous and life-renewing. It is the place where you can lose, find, and lose yourself again, all in a day’s journey. It is where Red Riding Hood ventured, Hansel and Gretel were lost, Snow White was abandoned, the Handless Maiden was nourished. It is full of wolves, bears, lions, elves, witches, fairies, foxes, brambles, hidden springs. It can be as dark as night and then, quite suddenly, a beam of sunlight can break through a broken-glass pattern of branches overhead. Then darkness resumes.

There was nothing to alarm him at first entry. Twigs crackled under his feet, logs tripped him, funguses on stumps resembled caricatures, and startled him for the moment by their likeness to something familiar and far away; but that was all fun, and exciting. It led him on, and he penetrated to where the light was less, and the trees crouched nearer and nearer, and holes made ugly mouths at him on either side.

Everything was very still now. The dusk advanced on him steadily, rapidly, gathering in behind and before; and the light seemed to be draining away like flood-water.

Then the faces began.5

As seen through the eyes of gentle, domesticated Mole (above), or as experienced vicariously through the challenges of Vassilisa in Baba Yaga’s mysterious wood, the forest conveys the primordial energy of the gods and goddesses, creators and destroyers, of old. Perhaps we sense, at least at the level of the unconscious, the crackling vitality of the wood wide web.

(Cross-posted at Luna Station Quarterly)

Image Credit: Prawny at Pixabay.com, illustration by Arthur Rackham, Creative Commons License

- Wohlleben, Peter. The Hidden Life of Trees (Vancouver: Greystone Books, 2015), 10-11.

- Porteous, Alexander. The Forest in Folklore and Mythology (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 2002 ), 13.

- Porteous, Alexander. The Forest in Folklore and Mythology (Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 2002 ), 32.

- Bettelheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales (New York: Vintage Books, 1989), 94.

- Grahame, Kenneth. The Wind in the Willows (London: Harper Collins, 1995), 61.