Cross-posted at Luna Station Quarterly as “Hair.”

My love of fairy tales includes those to which I might, as a feminist, be ashamed to admit—Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Rapunzel, Snow White. Simpering damsels? Victims rescued by a prince? I don’t think so. Their wildness, wisdom and strength cannot be denied.

My love of fairy tales includes those to which I might, as a feminist, be ashamed to admit—Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Rapunzel, Snow White. Simpering damsels? Victims rescued by a prince? I don’t think so. Their wildness, wisdom and strength cannot be denied.

It is sometimes called the ‘woman who lives at the end of time,’ or the ‘woman who lives at the edge of the world.’ And this criatura is always a creator-hag, or a death Goddess, or a maiden in descent, or any number of other personifications.1

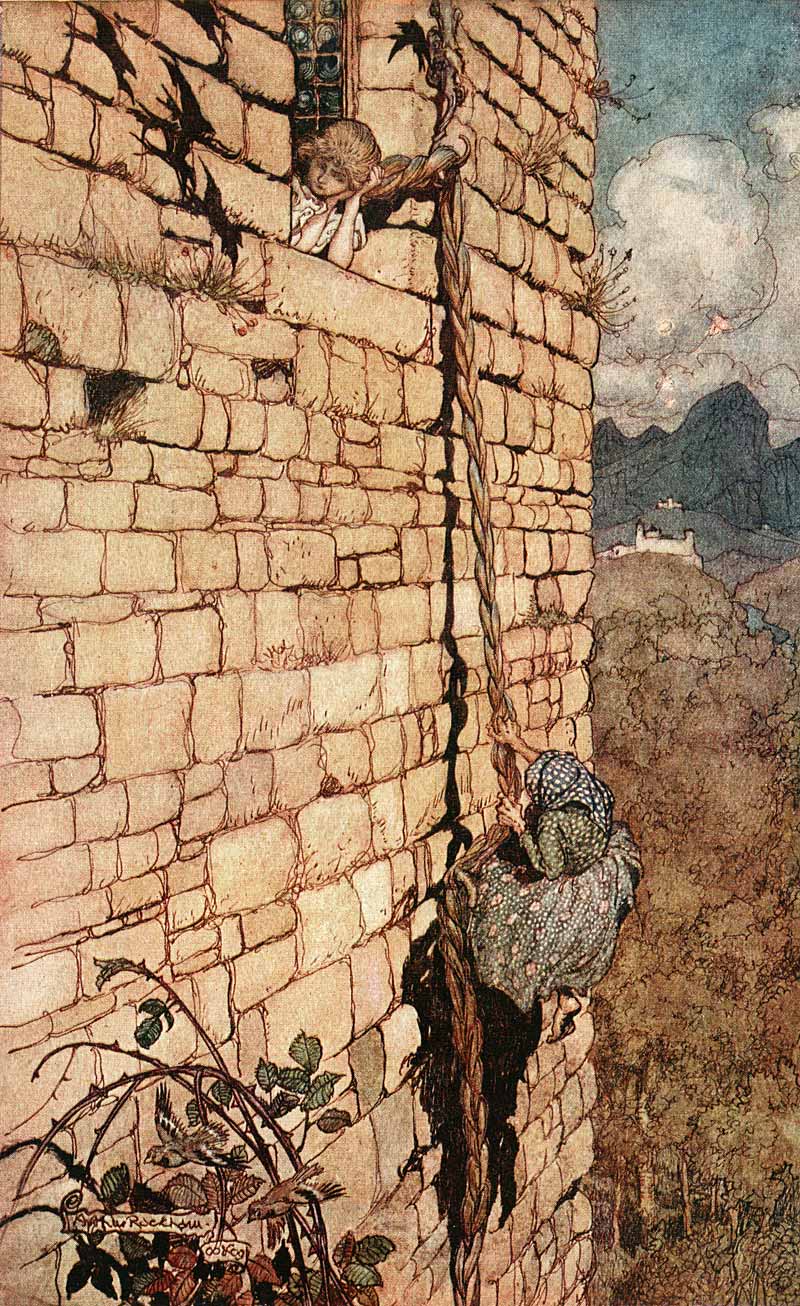

All four fairy tale heroines were isolated, set apart—out of jealousy in the cases of Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty and Snow White; from a hunger to preserve and control the one desired in Rapunzel. Jealousy is a common emotion. But the will to conquer a fellow being, to the point of keeping her entombed in a tower, is a different creature altogether. Though I love “Rapunzel,” I have always found the story deeply disturbing. And somehow, the emotional stew that has been my response to it includes wildly mixed reactions to the heroine’s most notable attribute: impossibly long hair. At various times in my life, I have coveted that hair, been astonished by the miraculous nature of it, or felt the wearer’s burden.

The dual notion of Rapunzel’s hair being both the source of her power and the means by which she is held captive speaks to the experience of being a woman without agency. Is there a woman alive who has not been the main source of strength for others while at the same time prevented from using that strength on her own behalf? Been the inspiration for others while her own creative endeavors aren’t thought worth valuing? While in the tower, Rapunzel is her captor’s raison d’être; hers is the only truly pulsing heartbeat within the stone-clad prison. Flowing hair is her banner, the exterior manifestation of an interior fire.

Hair is organic, but less subject to corruption than all our organs; like a fossil, like a shell, it lasts…In spite of its fragility, lightness, even insubstantiality, hair is the part of our flesh nearest in kind to a carapace. Its mythic power, its centrality to body language, and its mulitplicity of meanings, derive from this dual character: on the one hand, hair is both the sign of the animal in the human, and all that means in terms of our tradition of associating the beast with the bestial… on the other hand, hair is also the least fleshly production of the flesh. In its suspended corruptibility, it seems to transcend the mortal condition, to be in full possession of the principle of vitality itself.2

In The Interpretation of Fairy Tales, Jungian analyst and scholar Marie-Louise von Franz says, hair is “a source of magic power or mana.” And the combing or shearing of hair can symbolize the ordering or smoothing of powerful, often chaotic unconscious elements. In her experience, analysands new to the experience often dream of wild hair as their instinctive selves are let out of the gate.3

Rapunzel’s hair is absurdly, miraculously long; her secret power has always been present, potent. Her captor makes use of it, but only up until the time when the girl’s potential for action is awakened. In the tale, this occurs when a passing prince seeks her out. In the finer detail, it is Rapunzel’s actions that attract him in the first place. She rouses herself.

In The Annotated Brothers Grimm, Maria Tatar notes: rapunzel is “…an autogamous plant, one that can fertilize itself. Furthermore, it has a column that splits in two if not fertilized, and ‘the halves will curl like braids or coils on a maiden’s head, and this will bring the female stigmatic tissue into contact with the male pollen on the exterior surface of the column.’”4

Even her name signifies her potential, the secret fire that eventually blazes a new life, on her terms.

For further interest, a check of mythology and folklore reveals the following: hair can be 1) vitality (Samson), 2) transformation (Sif), 3) deadly power (Medusa), 4) life (Nisus, King of Megara), 5) sacrifice (Berenice and Ptolemy), 6) connection (calming the Inuit Sea Goddess Sedna by combing her hair), and 7) life-affirming power (Luthien, in a folktale created by J.R.R. Tolkien).5

Image Credit: Arthur Rackham [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- Pinkola Estés, Clarissa. Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype (New York: Ballantine Books, 1992), 9.

- Warner, Marina. From the Beast to the Blonde: On Fairy Tales and their Tellers (London: Random House, 1995), 372-373.

- von Franz, Marie-Louise. The Interpretation of Fairy Tales (Boston & London: Shambhala, 1996), 179-180.

- The Annotated Brothers Grimm. Tatar M, editor. New York (NY): W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. Rapunzel, 54.

- Hagey, Cathrin. “Hair,” accessed March 11, 2018, https://www.cathrinhagey.com/hair/.