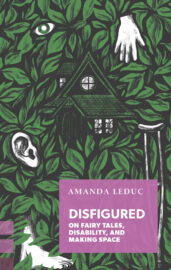

Amanda Leduc’s Disfigured: On Fairy Tales, Disability, and Making Space is an outstanding addition to the already wonderful collection of books about fairy tales and related topics. I was shaken and lifted up by what she has achieved by integrating disability justice with memoir, fairy tale studies, pop culture, and other fantastical and historical elements.

Leduc, a disabled Canadian novelist and essayist, prefers identity-first language. In describing her own love of fairy tales and the negative impact of realizing, at a very young age, that fairy tale princesses don’t walk with a limp, she is candid, funny, brilliant.

But it is never society that changes, no matter how many half-animals or scullery maids are out there arguing for their place at the table. It is almost always the protagonists themselves who transform society in some way–becoming more palatable, more beautiful, more easily able to fit into the mould of society already in place. The intervention is magical rather than surgical, but one can imagine the writers of these tales arguing in favour of the medical model [of disability]: the life-saving surgery, where life is synonymous with social standing and regard. The child who has surgery to repair their club foot is the same child who, in a fairy tale, would likely be visited by a fairy godmother or an evil witch, the gift of able-bodiedness dangled in front of them in a way that’s entirely irresistible.

We’ve come to associate the term Fairy Tale with a story that ends happily, for those who are deserving. Not just any story will do, as is the tradition. We have well-groomed expectations, going back hundreds, if not thousands, of years, about a fairy tale’s archetypal components: magic, wise women, villains, animal helpers, beautiful heroines, etc.

Disney has attempted to rectify the classic narrative arc of fairy tales in which an attractive, healthy, white hero or heroine achieves their happily ever after. But we need more than bandages and skin grafts to repair the damage done by excluding most of humanity. Nothing less than an entirely new body of literature will suffice.

Disability is a way of moving through the world, Leduc argues. Disability is not metaphor or a symbol for something else. Since the 1990s, the motto for the disability justice movement has been “Nothing about us, without us.”

Put another way: the medical model celebrates an individual’s triumph over disability, while the social model celebrates society’s collective power and responsibility to consider the needs of all, thus making disability an integrated element of the society in which we live.

We like to put ourselves in boxes, but life doesn’t really allow for it. Happiness, disability, illness, poverty and wealth: these things are inconstant, changeable. No one can survive without the collective efforts of society. Each of us requires practical/social/environmental adjustments in order to live our lives as we see fit. My happy ending likely doesn’t look like your happy ending, just as my body is also different from yours. So be it.

Sometimes, when happy endings and obvious villains are all that you’re fed, it becomes difficult to square your own experience of the world with that story. If you’re shown the different body as other over and over as a child, it becomes hard to see your own different body as something that might, in turn, belong.

This goes for bodies and children of all kinds. For myself, as a disabled child, it had a particular kind of staying power. Sometimes I feel like the bright colours and bright bursts of song in Disney films are as delicious and as deceptive as the witch’s candy cottage hidden deep inside the woods.

You might eat, but this kind of candy will never fill you up.

Disfigured has made me rethink my childhood reaction to the event in the children’s classic Heidi when the disabled girl Clara is forced to walk when her wheelchair is smashed. The upshot is that the real barrier to Clara being a “normal” girl was in her mind all along. Of course we were meant to cheer Clara on as she took her first, tentative steps. But what a different story it would be if Clara was perceived to be whole and well, as she was, wheelchair and all.

As with the charity model, psychological approaches to disability work to take the blame away from society and put it on the individual—to make disability not a lived, mundane reality but a temporary struggle that can be overcome if one has the inner and outer strength to do it.

Amanda Leduc not only mines traditional tales from the likes of the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen but also analyzes the influence of pop culture on our collective thinking. She offers an illuminating look at the facial scars of Bond villains, the limitations of Disney princesses, and the more contemporary hero narratives found in the Marvel Universe.

While doing a surgical investigation of fairy tales and their ilk, this author has whipped up some magic of her own. Disfigured goes to the heart of the stories we tell ourselves, whom we accept, and whom we other. It is both far reaching and deeply intimate–a book I highly recommend.